NYT crossword clues present a fascinating challenge, blending clever wordplay, intricate structures, and subtle misdirection. This exploration delves into the art and science behind these puzzles, examining the various clue types, techniques used to craft them, and the evolution of their style and complexity over time. We’ll uncover the secrets behind the seemingly simple yet often fiendishly difficult clues found in the New York Times crossword, providing insights into their construction and the strategies employed to solve them.

From straightforward definitions to cryptic puns and anagrams, we’ll dissect the grammatical structures and wordplay techniques that define NYT crossword clues. We’ll analyze the factors that contribute to a clue’s difficulty, exploring how misdirection, ambiguity, and unexpected twists challenge solvers. The evolution of clue-writing styles across different eras will also be examined, highlighting significant shifts in complexity and creativity.

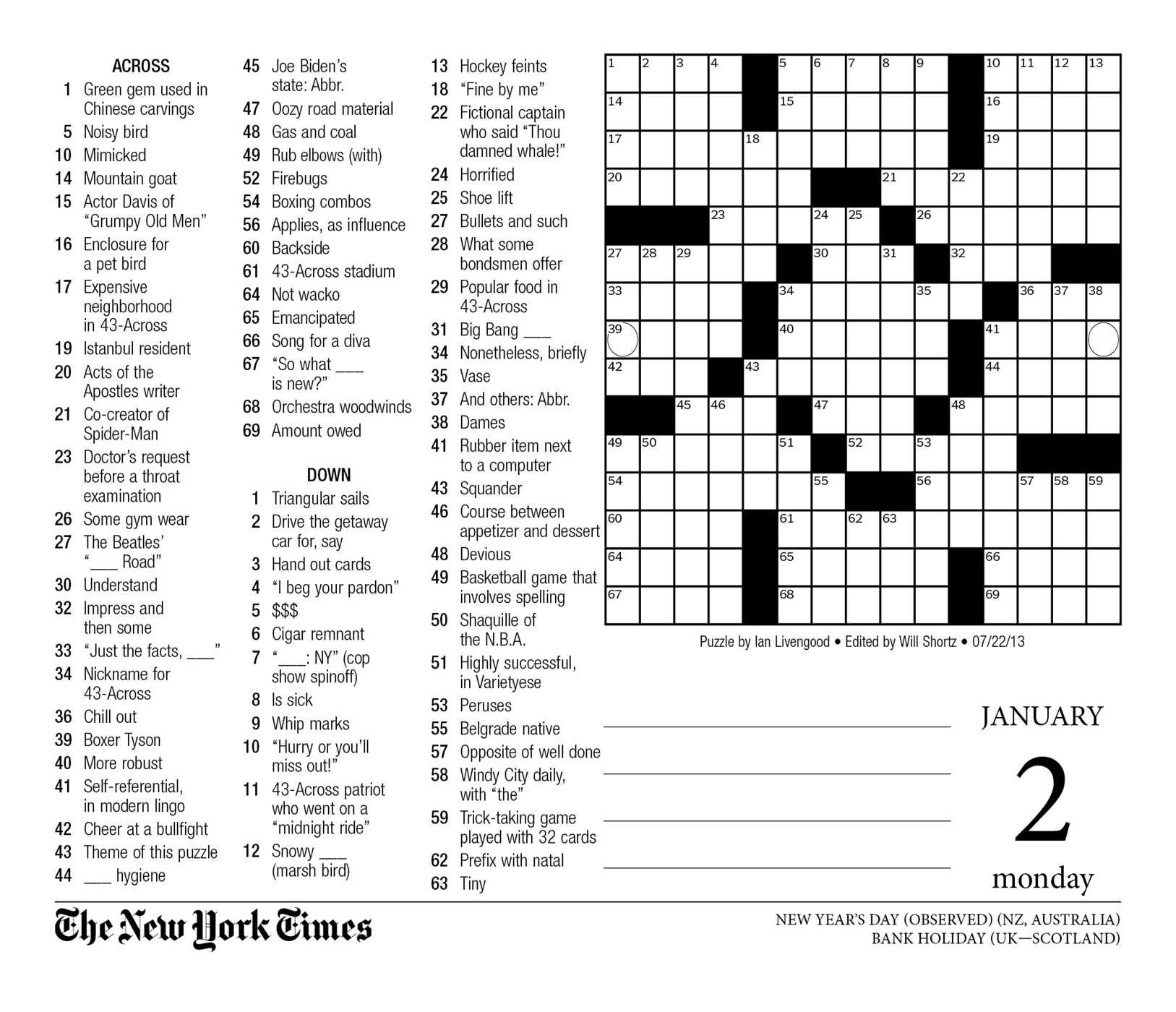

Finally, we will consider how visual representations can aid in understanding and solving particularly challenging clues.

Wordplay and Puns in Clues

The artistry of the New York Times crossword puzzle lies not only in its challenging grid but also in the clever wordplay embedded within its clues. Puns, in particular, are a cornerstone of this artistry, adding layers of complexity and delight for the solver. They transform the simple act of finding a word into a playful exercise in linguistic dexterity, demanding both vocabulary knowledge and lateral thinking.Puns leverage the multiple meanings or sounds of words to create ambiguity and challenge solvers.

Solving NYT crossword clues often requires lateral thinking, connecting seemingly disparate concepts. For instance, consider the challenge of finding a clue related to corporate restructuring; you might unexpectedly find yourself researching the complexities of businesses undergoing significant change, such as the recent mosaic brands voluntary administration. Understanding such events can surprisingly broaden your knowledge base and even improve your crossword-solving skills.

This ambiguity forces the solver to consider different interpretations of the clue, often leading to a moment of “aha!” when the intended meaning becomes clear. The inherent misdirection in a well-crafted pun is what makes it so effective. It compels the solver to move beyond the obvious, to explore the nuances of language and the potential for unexpected connections between seemingly disparate concepts.

NYT crossword clues can be surprisingly challenging, requiring a broad range of knowledge. Sometimes, even understanding the news helps; for example, recent business news, such as the mosaic brands voluntary administration , might provide a clue’s answer. Returning to the crossword, remember to consider wordplay and common crossword abbreviations for the most difficult clues.

Types of Wordplay in NYT Crossword Clues

Effective puns in crossword clues often employ various techniques to create the desired ambiguity and challenge. These techniques are frequently combined to increase the difficulty and satisfaction of solving. A strong clue might use an anagram, a hidden word, and a double meaning all at once.

Examples of Wordplay Techniques

The following list illustrates common wordplay techniques frequently found in NYT crossword clues, along with examples to demonstrate their application.

- Anagrams: Letters of a word or phrase are rearranged to form a new word or phrase. Example: “Disorganized rat” (10 letters) might clue “ARROGANTEST”.

- Hidden Words: A word is concealed within a larger word or phrase. Example: “Part of a sentence” might clue “RENT” (hidden within “sentence”).

- Double Meanings: A word or phrase has two distinct meanings, one literal and one figurative, which are both relevant to the clue. Example: “Something you might find on a ship’s deck” might clue “CARD” (referring to a playing card or a deck of cards).

- Homophones: Words that sound alike but have different meanings and spellings are used interchangeably. Example: “Sound of a bee” might clue “BUZZ”.

- Puns Based on Sound: Clues that exploit the similar sounds of words to create a pun. Example: “What a baker does with dough” might clue “KNEADS” (playing on the sound of “needs”).

- Cryptic Clues: Clues that employ a combination of wordplay techniques and often contain additional layers of misdirection, requiring solvers to decipher multiple layers of meaning. Example: “Upset stomach? It’s a sign of the times” might clue “CLOCK” (upset/reversed clock, sign of the times – telling the time).

The Role of Misdirection in Puns, Nyt crossword clues

Misdirection is crucial in crafting effective puns within crossword clues. It involves leading the solver down a seemingly logical path that ultimately proves incorrect, forcing them to reconsider their initial assumptions. This element of surprise and the subsequent “aha!” moment are key components of the satisfying puzzle-solving experience. A well-placed misdirection can elevate a simple pun into a truly clever and memorable clue.

For instance, a clue might use a common association to misdirect the solver before revealing the pun’s true meaning. A clue for “OVEN” might initially suggest a cooking appliance, but the actual answer might be a type of bird (“OVENBIRD”), relying on the similar sound to misdirect.

The Evolution of NYT Crossword Clues

The New York Times crossword puzzle, a daily staple for millions, has seen its clues evolve significantly over its long history. Early clues were often straightforward definitions, reflecting a simpler style of puzzle construction. However, as the puzzle’s popularity grew and solvers became more sophisticated, so too did the complexity and creativity of the clue writing. This evolution reflects not only changes in language and culture but also a deliberate effort by constructors to challenge and engage solvers with increasingly inventive wordplay.The shift from simple definitions to more complex and nuanced clues is a fascinating aspect of the puzzle’s history.

This transformation can be understood by examining the different styles and techniques employed across different eras. A comparison of clues from various decades reveals a clear progression in difficulty and stylistic choices.

Clue Styles Across Different Eras

Early NYT crosswords, from the puzzle’s inception in 1942, featured predominantly straightforward definitions. For example, a clue for “APPLE” might simply be “Fruit.” As the years progressed, constructors began incorporating wordplay, puns, and cryptic elements. The 1960s and 70s saw an increase in clues that relied on double meanings or indirect references. For instance, a clue for “OVEN” might be “Where pies are baked (and possibly burned).” This introduction of indirectness marked a significant turning point.

By the 1980s and 90s, cryptic elements became more prevalent, with clues often requiring solvers to decipher wordplay or hidden meanings. A clue for “REBUS” might be “Picture puzzle.” This shift reflects a growing expectation of a higher level of engagement and problem-solving from solvers. Contemporary clues frequently employ sophisticated wordplay, misdirection, and a deeper understanding of language and popular culture.

A recent clue for “MOSAIC” might be “Work of art with many small pieces, like this clue?”.

Notable Trends in Clue Writing Techniques

Several key trends have shaped the evolution of NYT crossword clues. One significant trend is the increasing use of misdirection. Early clues tended to be direct, whereas modern clues often lead solvers down a garden path before revealing the answer. For example, a clue might use a seemingly relevant but ultimately incorrect definition to mislead the solver. Another trend is the incorporation of contemporary references, ranging from pop culture to current events.

This reflects a desire to keep the puzzle relevant and engaging for a modern audience. The use of puns and cryptic elements has also become more sophisticated and integrated into the puzzle’s overall design. Early puns were often simple and obvious; today, they are frequently more subtle and require a greater degree of linguistic dexterity to solve.

Timeline of Significant Developments

| Era | Years | Key Characteristics | Example Clue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Era | 1942-1960s | Straightforward definitions, simple wordplay | “Fruit” for APPLE |

| Transitional Era | 1970s-1980s | Increased use of wordplay, double meanings, indirect references | “Where pies are baked (and possibly burned)” for OVEN |

| Modern Era | 1990s-Present | Sophisticated wordplay, cryptic elements, misdirection, contemporary references | “Work of art with many small pieces, like this clue?” for MOSAIC |

Mastering the art of solving NYT crossword clues requires understanding the nuances of language, the creativity of wordplay, and the subtle art of misdirection. This exploration has unveiled the intricacies of clue construction, from straightforward definitions to complex cryptic puzzles. By understanding the common structures, techniques, and evolution of these clues, solvers can enhance their skills and appreciate the craftsmanship involved in creating these engaging and intellectually stimulating puzzles.

The journey into the world of NYT crossword clues reveals a rich tapestry of linguistic ingenuity and creative problem-solving.

FAQ Explained: Nyt Crossword Clues

What is the difference between a cryptic and a straightforward clue?

A straightforward clue offers a direct definition or description of the answer. A cryptic clue uses wordplay, puns, or other devices to indirectly suggest the answer.

How are anagrams used in NYT crossword clues?

Anagrams involve rearranging the letters of a word or phrase to create the answer. Clues often include indicators like “mixed up” or “scrambled” to signal an anagram.

Are there resources available to help improve my NYT crossword solving skills?

Yes, many online resources offer tips, strategies, and explanations of common clue types. Additionally, practicing regularly is key to improvement.

What makes a clue particularly difficult?

Difficult clues often combine multiple wordplay techniques, utilize obscure vocabulary, or employ highly misleading phrasing. The level of difficulty also depends on the solver’s knowledge and experience.